This article was written by Ash Lennon, Kaimahi for Nature Restoration Team Leader. Recently the team have been working in Ōtāhuna.

There is a lot of mahi being done by Te Ara Kākāriki and other conservation groups in Canterbury in the hope that we can restore native biodiversity to this part of Aotearoa where so much has been lost. Te Ara Kākāriki hope to create enough green spaces between Banks Peninsula and the Southern Alps that we may see kākāriki make their way, in time, along a green corridor and re-establish themselves again on this side of the Canterbury Plains. There is also the Tui Corridor Project which hopes to create pockets of native vegetation between the Peninsula and Central Christchurch/Ōtāutahi, to encourage tui to grace the gardens and parks of the city once again. We might also expect, given time, the likes of South Island tomtit | ngirungiru and brown creeper | pipipi to start appearing in Ōtāhuna some time soon.

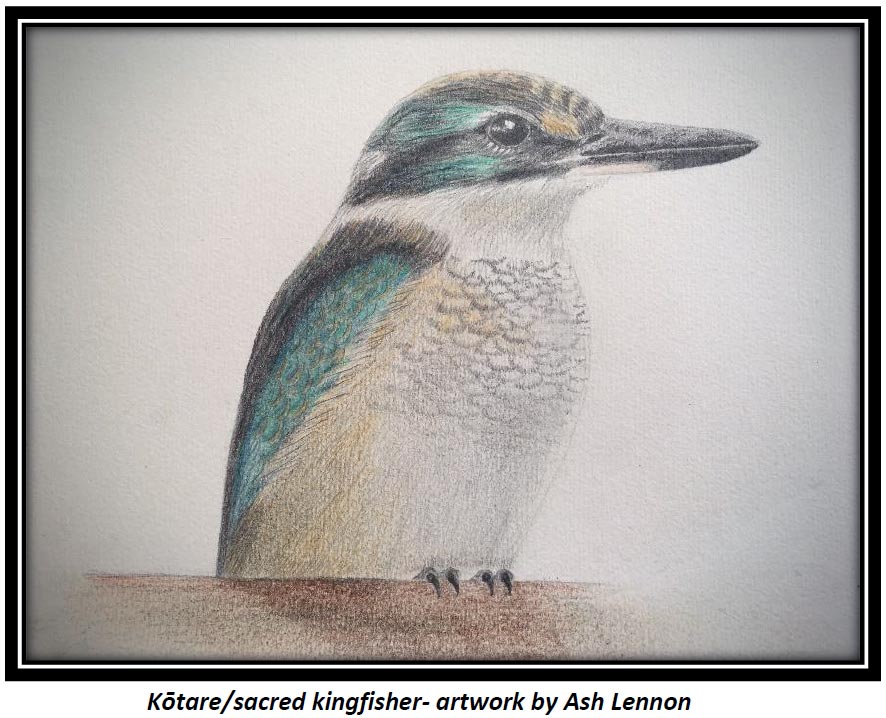

While these remarkable birds will be most welcome when they arrive, it is always good to remember that we have some incredible species already in Ōtāhuna and surrounds. So dependable are they, that we risk taking them for granted. One such resident is our native kōtare, or sacred kingfisher.

We’re lucky enough to be outside almost every day in Ōtāhuna, planting our way around the valley. No matter what site we are planting at, a day rarely goes by where we don’t catch a glimpse of, or hear the ‘kek-kek-kek-kek’ call of the kōtare | kingfisher.

Most of the world has kingfishers – with 86 species found worldwide on six continents. But having said that, within the world of birds they are a family that is unique. An extremely sharp and pointed bill, squat and stocky body and short legs make them instantly identifiable. They also have pretty interesting feet. While most birds in the world (not all) have three toes at the front and one pointing backwards (called anisodactyl), the kingfisher has a similar arrangement but has two of those toes fused together (called syndactyle)! This nifty adaptation is thought to give them extra hold when perching- which you can regularly see them doing on powerlines, trees and other structures. Their ability to hold still for long periods of time, along with their striking azure plumage, has made them the perfect models for countless pieces of art- the kōtare feather in the Tai Tapu Sculpture Garden being an beautiful example (although thankfully not lifesize!).

Kōtare were admired by Māori for their ability to patiently perch for long periods of time and led to the name of the elevated platform in a pā where a sentry would stand being referred to as the kōtare.

The world’s kingfishers are amazingly varied. Giant, dwarf, pied, azure, striped, banded, belted – they come in a seemingly infinite variety. So, what is so special about ours? Well, to start with, New Zealand has two species: our native kōtare, which is found on all main islands, and the introduced laughing kookaburra (that’s right, the kookaburra is a kingfisher!) found only in Northland.

Our native kōtare is a sub-species of the same kingfisher which is also found over much of the Pacific. It has been in Aotearoa, and quite possibly Ōtāhuna long before humans ever thought about coming here and has managed to adapt to the environment that humans created when they cleared much of the forest. Food for a kōtare comes in many shapes and sizes. While we often think of them as eating fish (as the name suggests), they have a varied and adaptable diet including lizards, tadpoles, earthworms, dragonflies, wasps, cicadas and beetles – just to name a few! They also regularly catch and eat mice, making them a welcome ally in the effort to reduce rodent numbers.

Like many of Aotearoa’s native birds, kōtare and their young are vulnerable to introduced predators, especially feral cats. They lay their eggs between October and January, in a nest which they make either in a hole in a tree or on the bank of a river – and even the top of a slip. They don’t have a pile of twigs and feathers for a nest like many other birds. Kōtare have a tunnel which leads to a chamber where they lay their eggs. This tunnel and chamber is built by the bird repeatedly flying at the earth and using their amazingly sharp beak to create a hole. Once big enough for them to climb in, they excavate the rest using their bill and funny little feet.

Now is an excellent time for us to really work on reducing predator numbers in time for spring and the nesting period for kōtare and most of our other native birds. While the kingfisher will do its duty by eating its way through many mice each day, we’ll try and repay the favour by checking our traps as often as we can. It’s the least we can do for this dependable and incredible bird. Hopefully we’ll continue to get daily visits while working in Ōtāhuna from one of its oldest and most charming residents.

If you’d like to play your part in reducing predator numbers to help the kōtare check out our pest management resources.