This news story has been adapted from an article published in the Ōtāhuna landowner’s newsletter. It was written by by Ash Lennon, Kaimahi for Nature Restoration Team Member with input from Peter Joyce.

As you travel along Rhodes Road or Heaton Drive in the Ōtāhuna Valley, you may start to notice regiments of plant guards that are marching over the hillsides. As well as the top of the valley that is regenerating into native bush, the landowners of the area are busy, with help from Te Ara Kākāriki and others, planting areas of native biodiversity to create spaces for our wildlife. With many landowners having created their own ‘Greendot’ sites over the last two years, and many more being added to in size, we thought it might be a good time to have a look at how long it will take for that paddock of saplings we’ve left you with to turn into a forest of giants.

One of the myths often repeated about New Zealand’s trees is that they are slow-growing. Nothing could be further from the truth. While admittedly, there are a few native species that do take their time to reach maturity and gain altitude, such as matai, there are a great number of species that grow at a surprisingly fast pace. The species that Te Ara Kākāriki are planting are those which will provide habitat for native creatures, but also quickly grow and establish a canopy.

To anyone who has planted native trees, this is not new information. In one year of planting mānatu/ribbonwood, hohere/lacebark, tarata/lemonwood or a multitude of other native trees, they would know that in anything like favourable conditions they can go from a plant 40cm tall to head height. But how do we know who are the quickest to grow, and out of our native trees, which we should plant to quickly establish a canopy?

Luckily for us, there are people who measure the growth rates of trees and help us to dispel the myth of slow-growing natives. At the Tai Tapu Sculpture Garden, where the planting of native trees has transformed a once grassy paddock into a sizable mix of native New Zealand trees, Peter Joyce has begun measuring the rate at which different species are growing.

Peter explained to us that at the Tai Tapu Sculpture Garden, the mānatu and hohere were the quickest growers at the beginning and have grown to at least 10m since 2012. However, in the last 7 or 8 years, the most notable growth has been taken up by some of the other species.

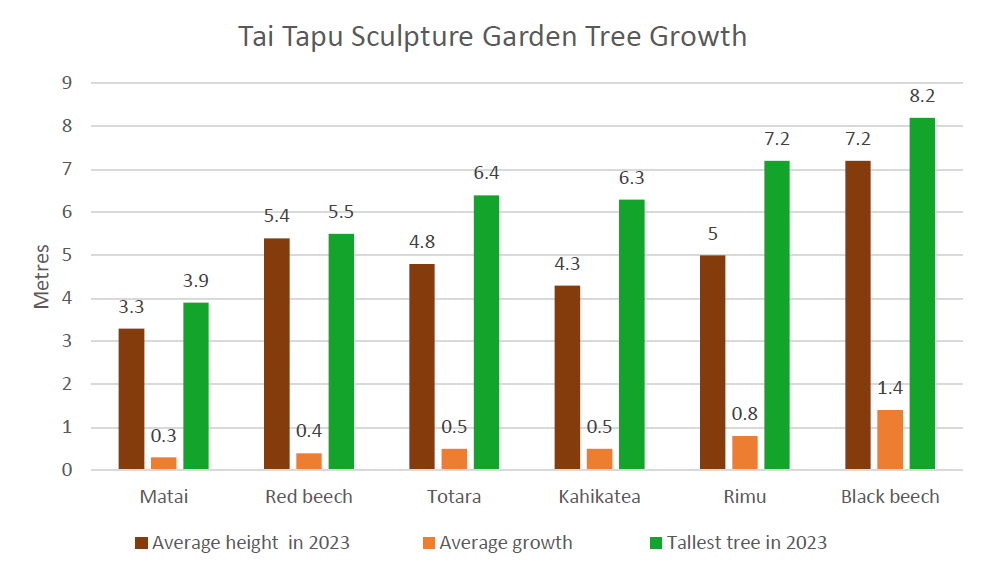

In July 2022 Peter decided to start measuring tree growth within the sculpture garden. Most of the selected trees had been planted between 2010 and 2012; so, most were 10-12 years old. Using a phone app called Arboreal, 51 podocarps including beech were measured in July 2022, and then again, in July 2023.

While the slowest grower was matai with an average of 0.3m that year, it still grew at the very upper limits to what the books say it can grow in optimal conditions. The most intriguing and startling growth, however, is in black beech. From July 2022-July 2023, the black beech measured in the Sculpture Garden grew an average of 1.4m!

While beech and rimu trees have been planted at a few sites around Ōtāhuna, they do not commonly occur there naturally. Te Ara Kākāriki only plant beech in the foothills of the Southern Alps and do not include rimu on any of our planting plans.

Beech trees share an interesting relationship with a group of fungi, known as mycorrhizae. These fungi live on the roots of trees where they take sugars, in return aiding the beech tree by providing minerals that the fungus can extract from the surrounding soils. This could have implications where we are attempting to restore beech forest as the micorrhizal associations may be absent, affecting the reestablishment of seedlings.

While all this is extremely interesting to self-confessed tree huggers like us here at Te Ara Kākāriki, it is worth hearing one final whakataukī- ‘He iti, he iti kahikātoa’. It translates as, ‘though little, it is still a mānuka tree’, or as is often also said, ‘size isn’t everything’.